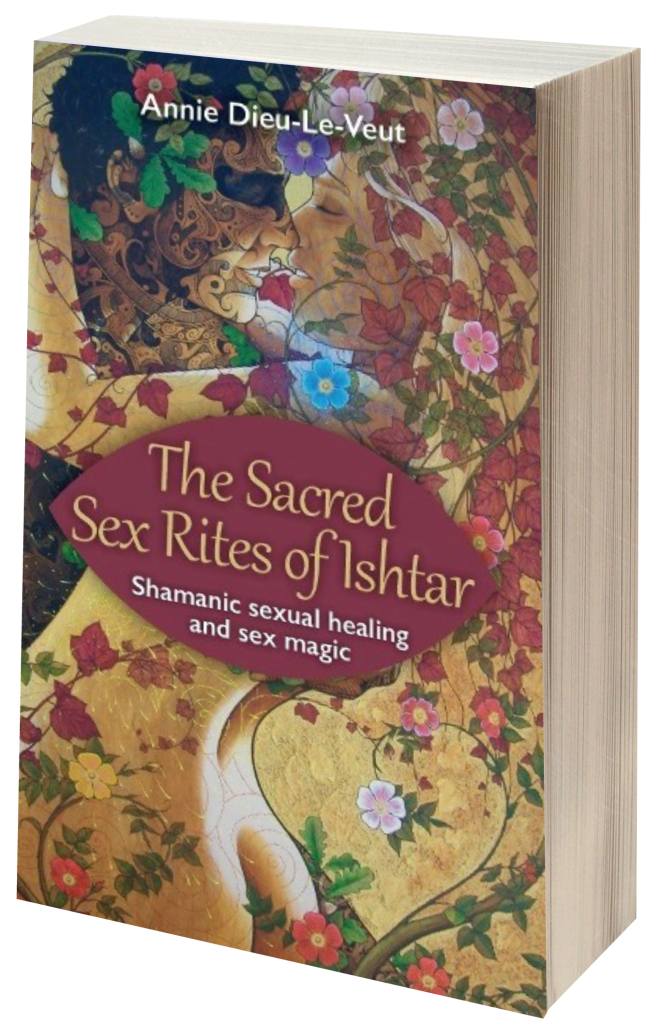

In my book, The Sacred Sex Rites of Ishtar, I devote a chapter to showing how Shakespeare used the vehicle of his play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, to provide an allegorical understory about the alchemical Marriage of the Sun and the Moon and the Birth of the Philosopher’s Stone. Here are the opening paragraphs…

As mentioned in the last chapter, I’m more aware of the fairies at certain times of the year, when the liminal walls between the dimensions become as fine as delicately spun cobwebs, thus enabling journeying between the realms to become easier, and for magical workings to become more potent.

Our early ancestors must have realised this phenomenon too, because these times coincide with the four Celtic cross-quarter holy periods – Imbolc in February, Beltane in May, Lughnasagh in August and Samhain in November.

I also find that these inter-dimensional boundaries are thinner during the periods of the equinoxes and solstices. And so I think it was no coincidence that William Shakespeare (whoever he really was) set his fairy play, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, at the time of midsummer otherwise known as the Summer Solstice, on June 21st.

I’m going to call Shakespeare “the Shakespeare writer”, because there is now so much controversy over who actually wrote those Elizabethan plays. Currently, we suspect the scribes were from among a group of Venetians within the court of Elizabeth 1st. I will say this, though: whoever wrote these dramas was extremely well versed in shamanic, magical and alchemical practices and also was cognisant in how those themes were transmitted in allegorical form within the ancient, traditional conventions of sacred theatre Mystery Plays via the roaming caravan of the Commedia dell’arte.

It’s well known that A Midsummer Night’s Dream contains a play within a play, by which I’m referring to the amateur dramatics of Peter Quince’s Pyramus and Thisbe. But what’s not so well appreciated is that it’s a play within a play within a play – a dream within a dream within a dream – like fractals nestled one within the other.

And this would have only been recognised by those who had the eyes to see well enough to be able to read the alchemical understory.

A shamanic journey is like a dream. Or perhaps a better way of putting it is that it’s like dreaming while awake.

And so that the play of A Midsummer Night’s Dream was seeded with motifs and keys to enable that journey, in the form it has come down to us, is a most generous gift from whoever wrote it, especially as they had to suffer the slights and stings of the pointed critiques from the ignoratti.

It’s clear to anyone familiar with alchemical magic that the Shakespeare writer developed his ideas for A Midsummer Night’s Dream from occult lore. But he ran into the same criticisms with this play as Mozart did with his opera also based on mystical allegory, The Magic Flute. They were both accused of triviality and slightness.

The 17th century diarist Samuel Pepys described A Midsummer Night’s Dream as “the most insipid, ridiculous play that ever I saw”.

Perhaps the reason these allegorical works got such a disdainful reception from the critics is because, by the 17th century, the original purpose of the art of the travelling storyteller, which was to disseminate the seeds of the magical and shamanic mystery teachings, had been lost. The so-called, but badly mis-named, Age of Enlightenment was on the rise among intellectual thinkers, with its emphasis on concrete realism and scientific rationale that could find no place for imagination and mystery.

The Shakespeare writer composed A Midsummer’s Night’s Dream earlier than the so-called Enlightenment but even then, it would have been impossible for the ordinary audience member to have been able to recognise and appreciate such a rich and vibrant seam of brilliant allegorical gold running through its sub-stratas without having some knowledge of the Mysteries. While we’re aware of John Dee as Elizabeth I’s court astrologer and alchemist, that kind of knowledge tended to remain in the royal courts, in medieval times, where it could be controlled. Most alchemists, in those days, were either in the pay of the monarchy or were locked up in prison.

So, these multi-layered, sweetly-honeyed baklava cakes of storylines containing metaphors representing magical and shamanic thought could find no foothold in the collective consciousness then, much like now, because they didn’t make rational or logical sense. Magic isn’t rational or logical — or possibly there once was a rationale for, say, why the Queen of the Fae presents the Underworld initiate with an apple, with the reason for it being long lost in the mists of time. But there equally well may not have been. Logic proceeds from logos, which was established as a formal discipline by Aristotle, who, scholars believe, had never been initiated into the Mysteries.

That Western thinking is largely predicated on Aristotelian logic is partly why we experience such culture shock when visiting India, which doesn’t have that tradition behind its thinking. India had managed to thrive quite successfully for millennia without it… until it was introduced by the Buddhists and Jains and, to this day, it still hasn’t got much of a foothold in the more remote parts of southern India.

As Nick Bottom says to the Faery Queen Titania in Act III:

“… to say the truth, reason and love keep little company together now-a-days; the more the pity that some honest neighbours will not make them friends.”

However, it doesn’t matter whether the rationale behind these magical stories is lost or never was because to follow this path we don’t need to know the logical reason behind the magical keys and what they mean. They are like glyphs or pictures drawn with fairy ink in our blood or in our DNA. They are stamped in our race memory, almost like barcodes, and when activated by the right kind of sound or imagery, through stories, songs and plays, a longing comes alive within us to search for what we’ve lost.

Public performances of these sorts of plays and operas have always served that need. It has been the traditional role of the wandering storyteller from time immemorial.

It is obvious that the writer of A Midsummer Night’s Dream would have been familiar with magical texts because storylines from them appear in some of the other plays of the Shakespeare scribe. For instance, in Macbeth, there is a prediction from the subject of the poem introducing our preceding chapter, the 13th century diviner Thomas the Rhymer who was granted a boon by the Faery Queen.

Fedderate Castle sail ne-er be ta’en

Till Fyvie wood to the seige is given

So let’s start to take a look at some of the traditional magical keys and motifs in A Midsummer’s Night Dream, to see what sort of self-transformative, magical journey the Shakespeare writer wanted to take us on.

That was an extract from Chapter 4, The Magic of a Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Sacred Sex Rites of Ishtar, which you can get on Amazon where the e-book version is currently being sold for free, as a loss-leader for its Kindle Unlimited promotion, until July 25th 2023.

Need more like this?

You’ve just read an article by Annie Dieu-Le-Veut, the author of The Sacred Sex Rites of Ishtar.

To get this book, just click here to be taken to where you can buy it on Amazon.

Available in paperback or for your Kindle.

Comments